What You’ll Learn in This Post

- How to distinguish between the two main structures of clouds

- How to classify clouds based upon their height

- Pros and cons of “three basic types of clouds”

- Types of clouds that don’t fit into the “three types of clouds” model

Introduction

Have you ever seen a cloud that looks like a rabbit or an elephant? Maybe a cat or a dog? The formal names for clouds sound a bit more sophisticated, as they’re derived from Latin. You might be familiar with cumulus, stratus, or cumulonimbus clouds. But how do we classify clouds, and where did these names originate?

Table of Contents

The Origin of Cloud Classification

The man pictured above is Luke Howard (1772-1864), a British chemist and amateur meteorologist most well-known for developing the cloud classification system that is still in use today. He used a small set of Latin words, rearranged in various combinations, to describe cloud appearance and height. Other cloud classification systems were preposed before and after his time, but his naming conventions have stuck.

How can I learn more about Luke Howard? (Click to expand)

A great book about Luke Howard’s life and his development of the cloud classification system is The Invention of Clouds by Richard Hamblyn. The book also paints a vivid picture of scientific community in London at the turn of the 19th century.

Basic Cloud Structures

The two basic structures of clouds are cumulus (cumuliform), which translates as “heap”, and stratus (stratiform), or “spread-out”. Cumuliform clouds are lumpy, like small cotton balls, while stratiform clouds are layered, spreading out over large portions of the sky. Both cumuliform and stratiform clouds can occur throughout the depth of the troposphere. The higher the clouds, the smaller (cumuliform) or thinner (stratiform) they appear. Most clouds generally take on either a cumulus-like or a stratus-like appearance.

Cloud Classification by Height

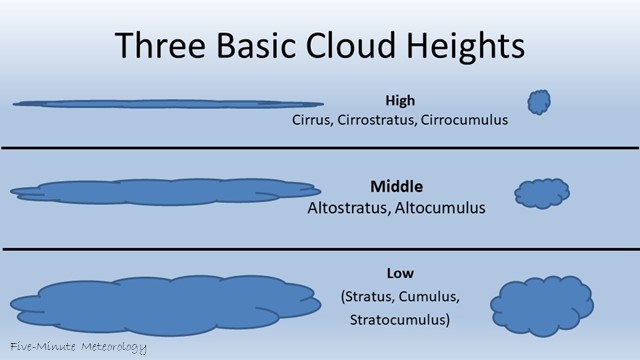

Clouds are further classified based upon their height above the ground. Cumulus, stratus, or stratocumulus clouds appear low in the sky. Stratus clouds can sit at ground level in a phenomenon that we call fog. Stratocumulus clouds have characteristics of both stratus and cumulus clouds, appearing as a dark layer interrupted by spaces of lighter, thinner clouds in between. Viewed from above, stratocumulus clouds are lumpier on top than stratus clouds.

Clouds at mid-levels adopt the prefix of “alto-“, much like the alto is a middle voice in the choir, below the soprano. The two cloud types that occur at mid-levels are altocumulus and altostratus. Rather than appearing in isolation, altocumulus clouds appear as fields of small cotton-ball clouds forming a canvas across the sky. Often, a wide area of altostratus cloud fades to patchy altocumulus at its edges.

What did the cumulus cloud say to the stratus cloud? (Click to expand)

“What’s up with you always being so low-key, Stratus?”

“Well, Cumulus, I like to keep things on the down low. Unlike you, always puffing up and making a big scene!”

Below is a table of approximate pressure values and heights corresponding to different cloud heights. These numbers are merely estimates: clouds don’t follow rules when it comes to how high they should be. In a few posts, we will apply this table to look at clouds and to use data to estimate their height.

| Pressure | Height | Possible Cloud Types |

| 1000 – 750 mb | 0 – 6500 ft 0 – 2000 m | Cumulus, stratus, stratocumulus |

| 750 – 400 mb | 6500 – 20,000 ft 2000 – 6000 m | Altocumulus, Altostratus |

| 400 – 100 mb | Above 20,000 ft Above 6,000 m | Cirrus, cirrocumulus, cirrostratus |

High-level clouds use the prefix “cirro-“, adopted from cirrus clouds, which are wispy, streaky, and hair-like in appearance. Clouds at higher elevations appear smaller, especially those with cumuliform structure. Cirrostratus clouds are faint white sheets covering the sky. They’re more easily seen near the Sun during the day and near the Moon at night. Cirrocumulus clouds are tiny cotton balls peppered across the sky. All cirriform clouds are composed of ice crystals contributing to their feathery appearance.

Recap: Clouds are classified based upon their structure (cumuliform or stratiform) and their height (low, middle, high).

Are there really three basic types of clouds?

Yes and no. Many websites simplify cloud classification by stating that the cloud types boil down to cumulus, stratus, and cirrus (or, perhaps more accurately, cumuliform, stratiform, and cirriform). These three terms encompass the cloud structures that we see, but we add a fourth cloud type (nimbus) when a cloud produces precipitation.

By combining different terms, as is described below, we end up with 10 main cloud types. But even then, real clouds morph over time. Sometimes, clouds can display characteristics of two different cloud types at once. So in short, if you want to boil clouds down to their simplest terms, then yes, three terms covers the range of possibilities quite well. But if you want to describe the intricacies of clouds, you need to develop more complex terminology.

Other Cloud Types

One other Latin word is used in the cloud classification system: “nimbus”, for rain. Nimbostratus is a layered rain cloud, at low to mid-levels. Cumulonimbus is the term for a tall, lumpy thunderstorm cloud. There are ten primary cloud types in all. You can learn how to make your own cloud type observations on the GLOBE website.

What about those streaky clouds I see across the sky from airplanes? (Click to expand)

Those are contrails – short for condensation trails. They only form when the temperature and moisture conditions in the upper troposphere are sufficient to form ice crystals when the hot, moist jet exhaust mixes with the cold, drier air behind the plane. If the atmospheric conditions remain supportive of ice crystals, the contrails can remain in the air for hours and travel long distances, driven by fast upper-level winds. Eventually, the contrails dissipate due to turbulent mixing with dry air.

There are many great websites that describe the various cloud types in much more detail, so there’s no need to re-hash them here. I recommend this external Cloud Identification Guide as a great resource. The World Meteorological Organization’s International Cloud Atlas contains many cloud photos and drills down into more specific cloud classifications.

Key Takeaways

- Clouds are classified based on appearance (structure) and height in the atmosphere.

- There are two main structural types:

- Cumuliform clouds are lumpy or puffy, like cotton balls.

- Stratiform clouds are flat and layered, often covering large areas of sky.

- Cloud names are derived from Latin roots. For example, “cumulus” means heap, and “stratus” means spread out.

- Height-based prefixes help us locate clouds in the atmosphere:

- Low-level clouds don’t use a prefix (e.g., stratus, cumulus).

- Mid-level clouds use “alto-” (e.g., altocumulus, altostratus).

- High-level clouds use “cirro-” (e.g., cirrocumulus, cirrostratus).

- Cirrus clouds (and other cirro- types) are made entirely of ice crystals, giving them their wispy appearance.

- Nimbus means rain. If you see “nimbus” in a cloud name, it’s either producing precipitation or capable of doing so.

- Thunderstorm clouds are called cumulonimbus: their base is near the ground, and they can tower over 50,000 feet tall.

- Luke Howard, a British chemist in the 1800s, developed the cloud classification system we still use today.

Test your knowledge from this post with the practice quiz below.

In the next installment of Five-Minute Meteorology, we’ll look at how meteorologists plot data vertically in the atmosphere using a skew-T diagram.

You must be logged in to post a comment.